Roof Framing

Roof Angles, material, and the envelope to make a good Roof.

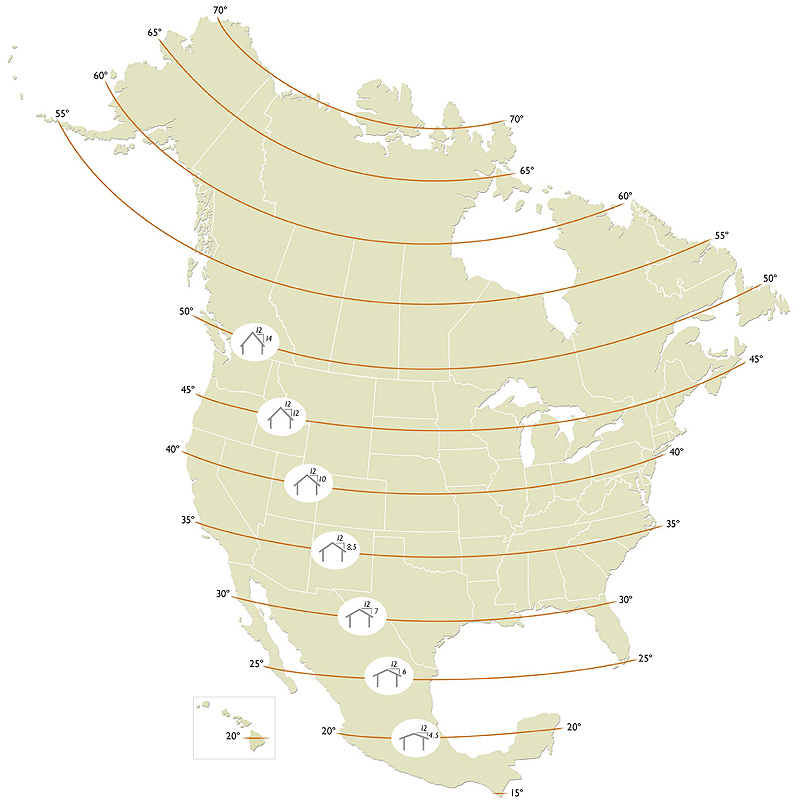

Roof Angles

In order to efficiently use passive solar heating or a roof equipped with solar panels, it's best to keep the house oriented within 30 degrees of south, if possible. Roof angles that are equivalent to your latitude optimize solar panel efficiency. This estimation is most accurate in the southern US, but the further north your home is located, this optimal roof angle will be about 5-10 degrees less than your latitude to optimize solar insolation. Size your overhangs to admit winter light while blocking the hot summer sun.

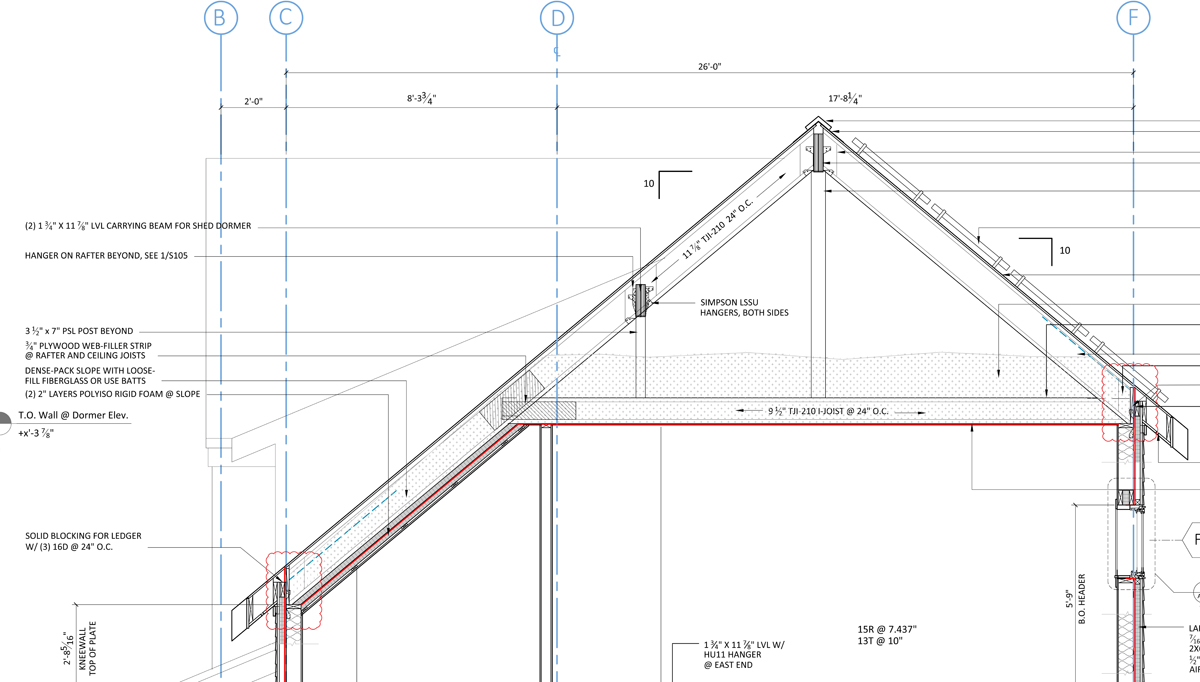

Framing Materials

Framing a roof is greenest with engineered lumber. Engineered lumber comes in various forms, including I-joists and laminated veneer lumber (LVL), both of which can be used for rafters. Because I-joists combine oriented strand board (OSB) webs with 2×3 flanges, they make good use of small trees and wood chips. Like plywood, LVL rafters are assembled from layers of veneer and glue. Because LVLs can be ordered in almost any length, they are particularly useful for buildings that have long spans. Conventional wide-dimension 2x10s or 2x12s that are sometimes used for rafters come from big trees and represent more raw material than alternatives such as roof trusses, I-joists, or structural insulated panels (SIPs). Yet the use of 2×10 or 2×12 dimensional lumber for roof framing may still make sense in regions of the country that have local sawmills. Delivery distances for dimensional lumber from local sawmills are short, saving transportation energy.

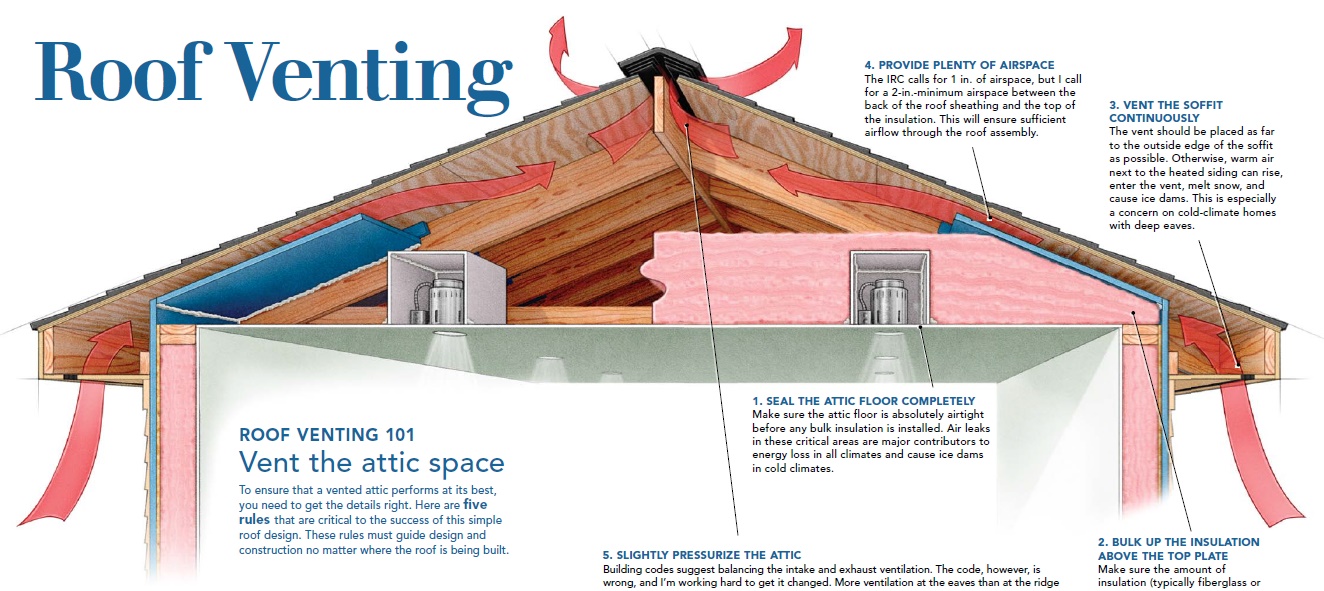

Venting & Insulation

Venting, insulating, and air sealing the roof and attic are possibly two of the most difficult details to get right in a house. Insulation may be in the roof, the attic floor, or even a combination of the two. The type of insulation may affect how the roof is constructed and may guide the selection of framing and sheathing materials. For example, radiant barrier sheathing may make sense when insulation is placed on the attic floor, but not when placed in the roof.

Vented

A vented roof is usually more forgiving than an unvented roof, and in many cases it's easier (and cheaper) to build it that way. Vented roofs are designed to cool attics, dry insulation, and prevent ice dams, among other things. The primary reason for venting a roof is to allow moisture to dissipate before it becomes a problem. Proper roof venting is still a complicated and hotly debated topic among performance builders, but the current consensus is to incorporate venting into your roof plan over a non-vented alternative.

Unvented

In some cases, an unvented (or "hot") roof is desirable, and there are ways to do it safely. This usually involves using closed-cell foam, in either sprayed or board form, so for carbon emission reasons we generally avoid hot roofs. Complicated roofs are difficult to vent. In some cases, an unvented roof assembly is the only one that will work, like in cathedral ceilings. Unvented roofs can perform well as long as they include thick insulation and are properly detailed to limit moisture transfer from the interior. Construction details vary depending on climate, but unvented roofs insulated with closed-cell spray polyurethane foam (specifically allowed by Section R806.4 of the IRC) can be used anywhere. One criticism of unvented roofs insulated with spray foam is that roof leaks may be difficult to detect, and could cause extensive roof sheathing rot before the homeowner notices any problems.

Insulation

For a vented roof assembly, blown in cellulose on the attic floor is the most recommended location for cost and performance reasons. Be sure to properly air seal any holes to the conditioned space below beforehand.

Spraying closed-cell polyurethane foam directly on the underside of the roof deck to form an air, vapor, and thermal barrier is a foolproof but expensive way to insulate cathedral ceilings and conditioned attics. Closed-cell foam is denser and heavier than open-cell foams, and also has higher R-values. According to a description of this technique by the Building Science Corp., a minimum of 1 inch of closed-cell foam acts as an air barrier, while a minimum of 2 inches creates a vapor retarder. Foam sticks very well to the roof deck and expands to fill cracks and voids that in a cooler areas might allow warm, humid air to reach the back of the roof deck and condense. In warmer climates, the foam blocks humid air from entering the house, where it could condense on cooler surfaces. Closed-cell foam can be combined with other types of insulation, such as fiberglass or cellulose, to get the benefits of an air or vapor barrier and to meet local energy guidelines at a lower cost.

The IRC includes requirements for roof ventilation in Section R806.

Resources

Fine Homebuilding - Roof Framing